With the largest Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak in history in West Africa and the first Ebola positive traveler arriving in the United States recently, many Americans are expressing concern over this lethal virus.

On top of that, over the weekend another African country, Uganda, reported a death due to Ebola’s relative, Marburg virus, and dozens of contacts are currently under observation.

I had the opportunity to talk to infectious disease expert, Tara Smith, PhD, Associate Professor with the Department of Biostatistics, Environmental Health Sciences, and Epidemiology at Kent State University’s College of Public Health, about Marburg virus and whether Americans need to be concerned over this Ebola “cousin”.

Robert Herriman: What is Marburg virus and what is its relationship to Ebola?

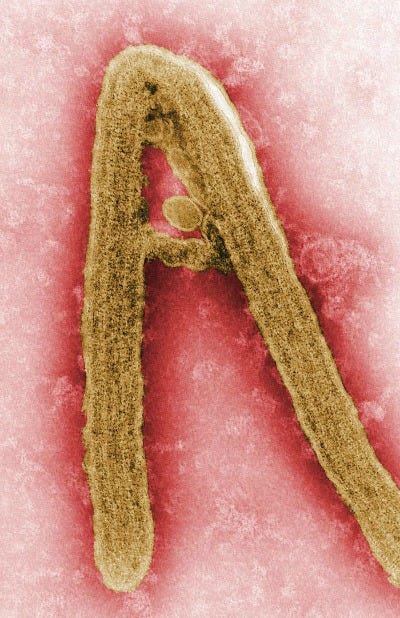

Dr. Tara Smith: Ebola and Marburg are two of the viruses in the family of Filoviridae—they’re “cousin” viruses, in different genera within the family. Both are RNA viruses and cause similar disease in humans, with the worst manifestation being the hemorrhagic fever that we’ve seen recently with the current Zaire ebolavirus outbreak.

RH: Is it found endemically anywhere in the world?

TS: Like Ebola, the reservoir for Marburgviruses appears to be bats, and particularly fruit bats. Bats have tested positive for Marburg in Kenya, Uganda, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Gabon—mostly fruit bats but also some species of bats that feed on insects. Marburg has also been found in non-human primates, who probably also acquired the virus from bats. In fact, when we first found Marburg in 1967, it was because the primate species that were being used in research in Germany were imported from Uganda and presumably infected with the virus in that country, and then it was transmitted it to humans.

RH: In what ways is it transmissible to humans?

TS: It seems to be transmitted in the same way Ebola is—via close contact with body fluids. As noted, the original outbreak was in a lab setting, and in that case most infections came from contact with infected animal tissues. There was also a fatal case in Russia in 1990 that originated from a laboratory exposure.

RH: Has a human with Marburg virus ever made it to the US? If so, how was it handled?

TS: We know of at least one imported case, in a woman who had traveled to Uganda and then returned to Colorado. She initially reported to an outpatient clinic and was sent home. Two days later, she went to her normal doctor saying she had diarrhea and abdominal pain, along with a few other symptoms. At this point she was admitted to a local hospital with hepatitis, nausea, and vomiting of unknown etiology. At this point she was even tested for Ebola and Marburg, but tests were negative. No particular isolation procedures were used with her, and she was discharged 10 days later. It wasn’t until a year after her hospitalization that she saw a story of a Dutch tourist who had visited the same caves in Uganda where she had traveled, and later died of Marburg, that she requested additional tests and found that there was evidence of previous Marburg infection.

RH: With the news of an outbreak in Uganda, and the concern globally and in the US about Ebola, what simple statement would you make to readers about Marburg?

TS: Like Ebola, there is nothing for the average person in the U. S. to be concerned about, particularly with this outbreak. We know of a single case in Uganda, and other currently-well contacts of that patient who are currently being watched for symptoms. Uganda has actually been good about containing these outbreaks. They have had 2 previous outbreaks of Marburg and 5 outbreaks of Ebola, but all of them since 2007 have been relatively small. I would hope this one can be quickly contained as well.