Bioterrorism is an understudied field that is often lacking support in regards to national security. Efforts to avoid incidences that might involve bioterrorism are often overlooked by governments and security agencies, increasing the likelihood of devastating effects. Although bioterrorism attacks are not a commonly used method of terrorism (making up 21 incidents in the United States between 1970 and 2019), it is important to not rule it as a very real threat to the American public (Tin, Sabeti and Ciottone, 2022).

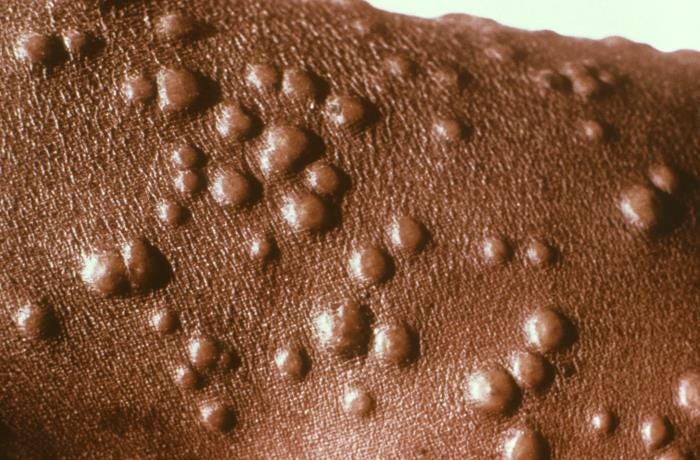

The Center for Disease Control (CDC) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) have compiled a list of nine Category A agents that are deemed to pose the “highest risk to the public and national security” (Minnesota Department of Health, 2022; Baylor College of Medicine, n.d.). Of these nine diseases, smallpox is arguably one of the most deadly amongst them due to its horrible symptoms, transmission rate, and high fatality rate. With a fatality rate of 30%, smallpox would decimate the United States’ population, causing an estimated 102 million deaths out of a current population of about 340.1 million individuals (The United States Census, 2025; World Health Organization, 2025b).

Smallpox vaccines were regularly administered amongst the US general public up until 1972, with the disease later considered to be eradicated in 1980 (Center for Disease Control, 2024a; enter for Disease Control, 2024c). Today, the only groups who get inoculated are military personnel or individuals who work with smallpox in laboratories, thus leaving the majority of the population to be completely vulnerable as a result of a bioterrorism event (Center for Disease Control, 2024c).

In the unlikely event of an attack, the United States’ possesses a national stockpile for smallpox vaccines as part of their smallpox preparedness plan, and although these numbers are not typically made readily available, it was estimated in 2022 that the national stockpile consisted over 100 million doses in order to help with the Monkeypox outbreak, as the smallpox vaccine an assist with preventing and addressing Monkeypox as well (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2022). Assuming that these figures are still accurate, this means that only about 29% of the U.S.’s current population could be inoculated.

With this frightening statistic, it is important to showcase how crucial it is to have the necessary resources and appropriate number of vaccines on hand should a bioterrorism attack occur. One instance where vaccines helped prevent a widespread smallpox outbreak was in 1947, when an individual who had visited Mexico fell ill on his trip back home to Maine and stopped off in New York City. Despite presenting symptoms of illness, he was not isolating and continued to go out for four days before being admitted to the hospital. He would go on to pass away 14 days after initially displaying symptoms with no diagnosis made at this time of death (Weinstein, 1947).

Shortly following the gentleman’s death, two individuals who were previously treated for different illnesses on the same floor soon returned to the hospital with similar symptoms, including a rash and fever. Biopsies on both individuals displayed the presence of smallpox and all known recent contacts of both individuals were vaccinated. As a result, over 6.3 million people were vaccinated within a three week period in New York City alone. Due to the quick actions of physicians and vaccine administrators, only 12 people developed symptoms; unfortunately, two individuals, including patient zero, lost their lives (Weinstein, 1947). The combined efforts of those administering the vaccine as well as the willingness of those exposed to be vaccinated greatly contributed to the successful containment of the outbreak.

Although this was true in 1947, should a similar event such as this occur today, the probability of having a similar outcome is very slim. As stated briefly above, one of these reasons would likely be due to the amount of available smallpox vaccines in the national stockpile today. While the exact number of smallpox vaccines available in 1947 was not very well documented, it can be inferred that since the U.S. public was regularly getting vaccinated against smallpox, there would be a greater number of vaccines on hand. Comparatively, a similar explanation can be assumed that since smallpox vaccination has not occurred regularly since 1972 and there are limited vaccines in the national stockpile, there would not be enough vaccines to protect the public in case of a bioterrorism attack.

In addition to the limited number of vaccines available today, there is also an increasing distrust of vaccines amongst the American public following the COVID-19 pandemic. This mistrust could lead to people declining inoculation should a bioterrorism event occur (Troiano and Nardi, 2021; GSK, 2023). However, although this is true, it is important to note that the majority of this hesitancy and distrust stemmed from a suspicion of rushed vaccine development and the belief by some that the disease was not as dangerous as authorities stated (Troiano and Nardi, 2021). Therefore, due to the smallpox vaccine being studied and distributed for over 200 years in order to hone its effectiveness and safety, this may allow for more trust towards the vaccine being distributed (World Health Organization, 2025a). If there remains a distrust towards the vaccine, it could still be possible to achieve herd immunity if at least 80% of the population were to be vaccinated, which would protect those who do not want to get inoculated (Kim, Johnstone, and Loeb, 2011).

Finally, transportation has advanced greatly, including the more commercialized use of airplanes since the mid-1950s (National Air and Space Museum, n.d.). Because of this, diseases are able to be spread much easier both domestically and internationally, causing a dramatically increased transmission rate, which has been shown to potentially “initiate or facilitate epidemics” (Sevilla, 2018; Findlater and Bogoch, 2018). For international flights today, the most commonly used airplane for an international flight is the Boeing 737 and can carry about 160 passengers, while the biggest airplane used on commercial flights is the Airbus A380, which can carry up to about 850 passengers (FlexAir, n.d.; EntireFlight, 2023). Therefore, on a typical international flight and with a transmission rate of approximately 60%, anywhere from about 96 to 510 passengers could contract the virus, spreading it to others in various locations (U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024b).

Although the likelihood of a bioterrorism attack is unlikely, it is important to examine smallpox outbreaks in the past, as well as current factors that suggest that preparedness is lacking and essential. It is in the American public’s best interest to strengthen vaccine stockpiles and improve public trust in immunization in order to help prevent a potential crisis.

Jess Peck is a recent postgraduate student with an MA in Human Rights, where she explored bioterrorism as a primary part of her research. With a passion for global health and human rights, she aims to produce impactful research that drives change to improve the lives of various communities.

Bibliography

Baylor College of Medicine (n.d.). Potential Bioterrorism Agents. Available at: https://www.bcm.edu/departments/molecular-virology-and-microbiology/emerging-infections-and-biodefense/potential-bioterrorism-agents#:~:text=Classification%20of%20Bioterrorism%20Agents&text=The%20CDC%20and%20NIAID%2C%20in,classify%20them%20into%20three%20categories. (Accessed: 21 March 2025).

EntireFlight (2023). The Most Common Airplane Types: An Exploration Across Various Aircraft Categories. Available at: https://www.entireflight.com/blogs/aviation-is-a-lifestyle/most-common-airplane-types#:~:text=One%20of%20the%20most%20common,different%20seating%20capacities%20and%20ranges (Accessed: 20 March 2025).

Findlater, A. and Bogoch, I. I. (2018). ‘Human Mobility and the Global Spread of Infectious Diseases: A Focus on Air Travel’, Trends in Parasitology, 34(9), pp. 772-783. Doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2018.07.004

FlexAir (n.d.). How many passengers can a commercial plane carry? Available at: https://aviex.goflexair.com/flight-school-training-faq/how-many-passengers-can-a-commercial-plane-carry (Accessed: 20 March 2025).

GSK (2023). New analysis shows lost ground on adult immunisation during the pandemic with 100 million doses potentially missed. Available at: https://www.gsk.com/media/10410/gcoa_ais-press-release.pdf (Accessed: 18 March 2025).

Kim, T. H., Johnstone, J., Loeb, M. (2011). ‘Vaccine herd effect’, Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases, 43(9), pp. 683-689. Doi: 10.3109/00365548.2011.582247

Minnesota Department of Health (2022). Bioterrorism Diseases. Available at: https://www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/bioterrorism/btdiseases.html (Accessed: 15 March 2025).

National Air and Space Museum (n.d.). The Evolution of the Commercial Flying Experience. Available at: https://airandspace.si.edu/explore/stories/evolution-commercial-flying-experience (Accessed: 20 March 2025).

Sevilla, N. L. (2018). ‘Germs on a Plane: The Transmission and Risks of Airplane-Borne Diseases’, Sage Journals, 2672(29), pp. 93-102. Doi: 10.1177/0361198118799709

The United States Census (2025). U.S. and World Population Clock. Available at: https://www.census.gov/popclock/ (Accessed: 17 March 2025).

Tin, D., Sabeti, P., and Ciottone, G. R. (2022). ‘Bioterrorism: An analysis of biological agents used in terrorist events’, The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 54, pp. 117-121. Doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2022.01.056

Troiano, G. and Nardi, A. (2021). ‘Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19’, Public Health, 194, pp. 245-251. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2021.02.025.

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2024a). About Smallpox. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/about/index.html#:~:text=Thanks%20to%20the%20success%20of,declared%20smallpox%20eradicated%20in%201980. (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2024b). How Smallpox Spreads. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/causes/index.html (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2024c). Smallpox Vaccine. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/vaccines/index.html#:~:text=In%20addition%2C%20the%20vaccine%20was,eradicated%20in%20the%20United%20States (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (2022). HHS Orders 2.5 Million More Doses of JYNNEOS Vaccine For Monkeypox Preparedness. Available at: https://public3.pagefreezer.com/browse/HHS.gov/01-01-2023T06:35/https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2022/07/01/hhs-orders-2-point-5-million-more-doses-jynneos-vaccine-for-monkeypox-preparedness.html (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

Weinstein, I. (1947). ‘An Outbreak of Smallpox in New York City’, American Journal of Public Health, 37(11), pp. 1376-1384. Doi: https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.37.11.1376.

World Health Organization (2025a). History of Smallpox Vaccine. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/history-of-vaccination/history-of-smallpox-vaccination#:~:text=Two%20months%20later%2C%20in%20July,to%20be%20vaccinated%20against%20smallpox.&text=Edward%20Jenner%20among%20patients%20in,Inoculation%2C%20coloured%20etching%20after%20J (Accessed: 17 March 2025).

World Health Organization (2025b). Smallpox. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/smallpox (Accessed: 14 March 2025).

Kate Sugak says smallpox was simply redefined to make the 'vaccine' 'work'. These days such lymphatic expressions are often labelled measles, chickenpox, monkeypox etc.

https://rumble.com/v1ld7nz-the-truth-about-smallpox-documentary-by-katie-sugak.html

Great article but I just wanted to correct one thing. Currently there are six Category A Bioterrorism agents as defined by CDC and NAID, not nine. See links here: https://www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/bioterrorism/btdiseases.html and https://biosecurity.fas.org/resource/documents/CDC_Bioterrorism_Agents.pdf